Table of Contents

Meet Charles Goodyear

Charles Goodyear (1800-1860)

Charles Goodyear improved upon the natural properties of rubber accidentally, and also accidentally advanced the cause of dentistry by leaps and bounds. His accidental invention eventually cost someone his life.

Improving vulcanization – it’s kind of a big deal

An antique Vulcanizer, the machine used to make Vulcanite dentures. Vulcanizer from the antique collection housed at Benco Dental’s dental museum in Pittston, Pennsylvania.

Goodyear had experimented with vulcanization – the process of turning raw rubber into a useful, pliable, and non-rotting material. Several others had been working on the process. He perfected his process of vulcanization in 1839 and received a patent for it in 1844. His brother, Nelson, figured out how to turn pliable rubber into a hard rubber material that he called Vulcanite, and received a patent for it in 1851. Another patent covering any resulting product, as well as the process itself, was issued to them in 1858. By this time, the Goodyear brothers and other companies licensed to make Vulcanite products were deep in patent infringement suits, suing manufacturers of hard rubber products who used the vulcanization process to make their goods. Throughout the 1850s and 60s, many companies manufactured all sorts of items made of vulcanized rubber, such as hand mirrors, photo cases, and jewelry. Vulcanized rubber became a precursor to modern plastics.

Antique Vulcanite earrings seen on Etsy.com.

Vulcanized rubber enters dentistry

This stuff is amazing! Hey Dentists, try it out!

One of the most revolutionary items made with vulcanized rubber was the base for dentures. Once dentists found this material and started using it, it ushered in what has been called “the era of false teeth for the masses” beginning in the 1850s. In 1848, Thomas W. Evans, the expatriate diplo-dentist, had used Vulcanite as a base for artificial teeth, and he made a Vulcanite denture for Charles Goodyear in 1854. Vulcanite could be easily molded onto a replica of the patient’s jaw, and the resulting base, once outfitted with porcelain teeth, would fit perfectly, was comfortable, and was created cheaply.

Antique Vulcanite denture.

You done changed the game, Charles Goodyear

It was seen as the greatest advance in dentistry in 25 years. Dentists everywhere started creating inexpensive dentures made of Vulcanite and prescribing them to their patients. Some dentists worried that the skill of dentistry and saving teeth would die out, as it was easier and cheaper to create dentures than try to save natural teeth. All the while, the manufacturers of Vulcanite seemed content to let dentists use the material without paying licensing fees, and when Goodyear’s original patent expired in 1861, dentists were convinced that any threat of paying royalties on dentures had ended. They would soon find out they were wrong.

A new player enters the game

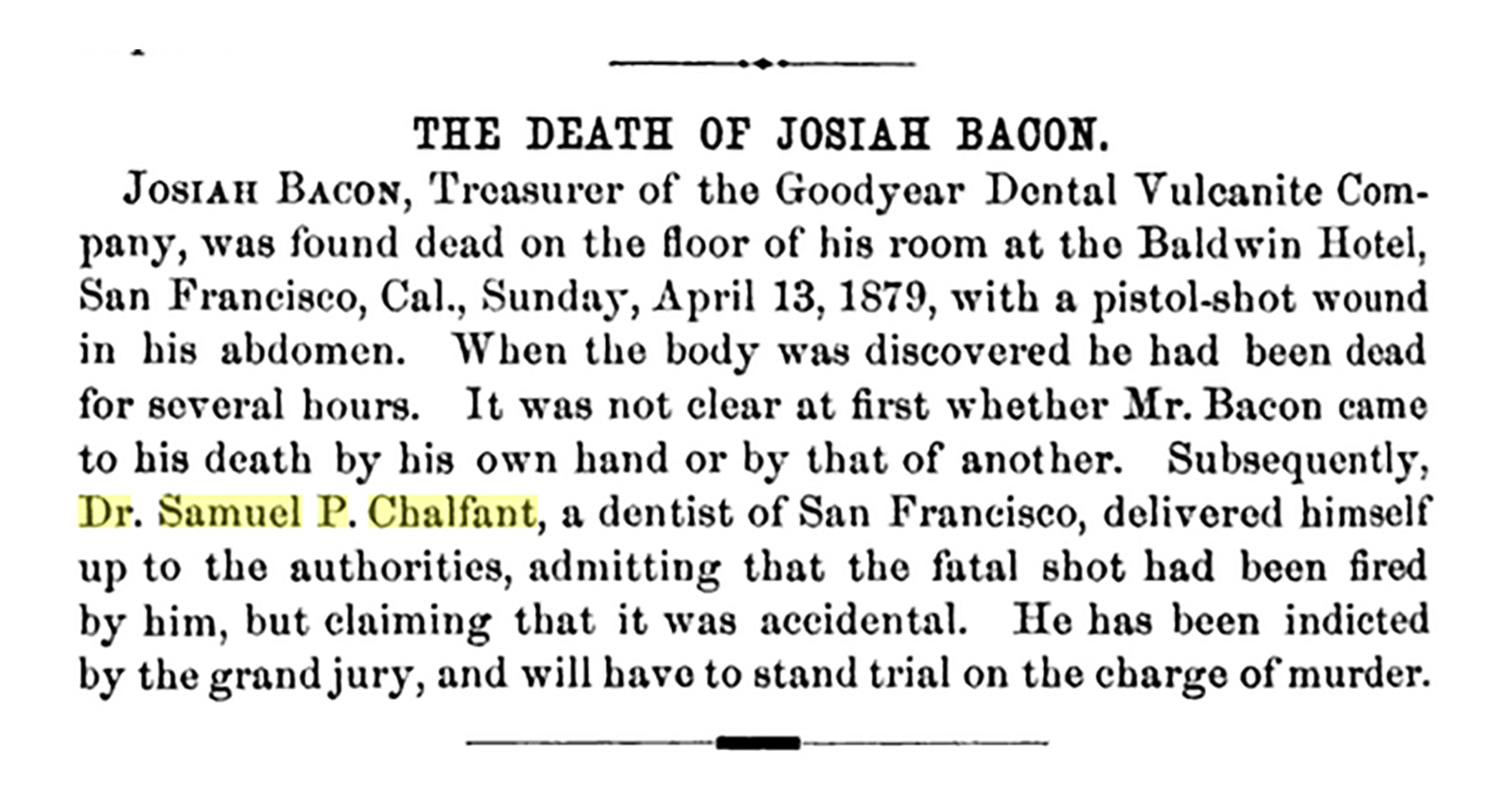

A Boston dentist, John A. Cummings, had been trying halfheartedly since 1852 to gain a patent for dentures made with material Vulcanized by the Goodyear process. The patent office routinely rejected his applications. In 1864, he sent in another, with the exact same specifications and drawings previously submitted. Inexplicably, the patent was granted. Some time after, Josiah Bacon, a businessman, who was treasurer of the Goodyear Dental Vulcanite Company, bought Cummings’ patent. Later, it was thought that Bacon was somehow behind Cummings’ patent success.

A clever way to bring home the Bacon

Bacon eventually controlled both the company and its patents and then used it all to his advantage. He set out to collect money from dentists who would need a license to create dentures from Vulcanite. Dentists were assessed fees of $25 to $100 per year, based on the size of the practice, in addition to a royalty fee of $2 for each denture of six or more teeth. Bacon began suing for patent infringement dentists who refused to pay, and from almost the beginning received favorable court rulings, obtaining judgments and injunctions. In 1866, he sued a slew of America’s most respected dentists. The profession responded by forming the American Dental Protective Society and appealing for funds to mount a legal defense and fight back against Bacon.

Bacon was ruthless and enlisted agents and spies to gather evidence against the dentists who didn’t fork over the required money.

The New York Times article reporting his murder in 1879 said that “one of his favorite methods of discovering infringements … was to employ a beautiful young lady, whom no dentist would suspect.… She was liberal with her money, and only particular on the one subject of the rubber. Once obtained, she had all the evidence requisite to enable Bacon to bring suit.” The same article says that “servants of dentists were bribed; next door neighbors were questioned, and intimidation was often resorted to.”

Patent trolling at it’s best… or worst

Bacon carried on for 13 years, collecting fees and mercilessly bringing lawsuits when dentists tried to get out of paying. While several groups of dentists tried to band together and fight the legal charges levied against them, they couldn’t prevail. As one despondent dentist reported, their group was “no match for a thoroughly organized Company composed of experienced, shrewd, and sharp businessmen.”

Dentists band together to stop Josiah Bacon

How do we stop this guy!?

Although the suits were filed in the name of the Goodyear Dental Vulcanite Company, those in the profession knew who the real villain was: “Josiah Bacon, the active and engineering Mephistopheles of this whole skinning raid upon the dentists,” in the words of one dental journal. Samuel S. White, of the S. S. White Dental Company, became a leader in fighting against Bacon. S.S. White’s publication, Dental Cosmos, closely reported on the trials and tribulations. Plans were made to mount an appeal to the Supreme Court challenging the validity of the patent. Then several dentists learned that the appeal had been denied. This effectively stopped others from trying to fight the patent. Further investigation revealed the appeal was a sham, engineered by Bacon himself to discourage others from fighting the company over paying the fees.

A first in Supreme Court History

The facts were brought before the justices, and for the first time in its history, the Supreme Court reversed itself, and vacated its affirmation of the lower court’s ruling, citing the deceptive nature of the appeal. This didn’t stop Bacon, it only stopped him from going after groups of dentists. He now went after them one at a time and with gusto.

Eventually, the appeal made its way to the Supreme Court again in 1877 and the decision went to Bacon – entitling him to all the money he collected in his lawsuits. This emboldened him, and in 1879 he set off on a cross-country business trip, filing lawsuits from Boston to San Francisco.

San Francisco City Hall, circa late 19th century.

Horse and buggy? Check! List of dentists for me to sue?Check!

Bacon arrived in the City by the Bay with a list of about 40 dentists he planned to sue. He had one doctor in particular who he was gunning for – Dr. Samuel P. Chalfant. Dr. Chalfant had been sued by Bacon at least twice before, each time running away from his lucrative practice rather than pay a licensing fee. Dr. Chalfant had moved to San Francisco to be as far away from Bacon as possible.

Chalfant — the next victim

Dr. Chalfant found himself in court, answering Bacon’s charges of patent infringement. He was convicted, and humiliated by Bacon, who was determined to make an example out of him. Bacon would pay for that humiliation the very next day.

A final showdown

Don’t mess with me, man!

Bacon instead became infuriated. During the dispute, Dr. Chalfant claimed the pistol fired accidentally, and Bacon, the man a historian later called “the Nemesis of the dental profession in the United States” was killed by a single bullet in the abdomen.

Dr. Chalfant later claimed that he went from the hotel directly to the local police station, but since it was Sunday, no one was there. He then hid for three days in a rooming house before surrendering to the police.

The Chalfant Court Hearing

Dentists everywhere contribute to Dr. Chalfant’s defense

At his trial, Dr. Chalfant was portrayed as a victim, a respected citizen driven to desperation by a vicious scoundrel, and dentists from all over the United States contributed funds for his defense. Convicted of second-degree murder, Dr. Chalfant was sentenced to 10 years at San Quentin, where he became the prison dentist. He served his sentence until 1883, when he tried to escape, and was recaptured. Dr. Chalfant served the remainder of his sentence and following his release, again took up the practice of dentistry in San Francisco, this time without the fear of prosecution for using Vulcanite.

… and the patent?

Goodyear let the patent run out on Vulcanite in 1881 and never renewed it. Presumably, nobody wanted to take a bullet to defend the patent. These days, hardly anyone remembers the murder, the patent wars, or how Vulcanite revolutionized the making of dentures.

The New York Times article reporting his murder in 1879 said that “one of his favorite methods of discovering infringements … was to employ a beautiful young lady, whom no dentist would suspect.… She was liberal with her money, and only particular on the one subject of the rubber. Once obtained, she had all the evidence requisite to enable Bacon to bring suit.” The same article says that “servants of dentists were bribed; next door neighbors were questioned, and intimidation was often resorted to.”

The New York Times article reporting his murder in 1879 said that “one of his favorite methods of discovering infringements … was to employ a beautiful young lady, whom no dentist would suspect.… She was liberal with her money, and only particular on the one subject of the rubber. Once obtained, she had all the evidence requisite to enable Bacon to bring suit.” The same article says that “servants of dentists were bribed; next door neighbors were questioned, and intimidation was often resorted to.”