As we prepare to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Lucy Hobbs Award, we reflect on Dr. Lucy Hobbs Taylor, the first woman in America to graduate with a dental degree and an instrument she most certainly had at her disposal – the tooth key.

At one point in her autobiography, written in the third person, Lucy discusses her rise to prominence, after so many trials and tribulations: “Her reputation widened, until all Iowa knew of the woman that pulled teeth.” The emphasis is her own.

Tooth Keys: A Painful Procedure

Tooth key on display in dental museum at Benco Dental home office.

Just what did she use to pull those teeth? Most likely, it was the humble tooth key, such as the one on display in the dental museum at Benco Dental home office in Pittston, Pennsylvania.

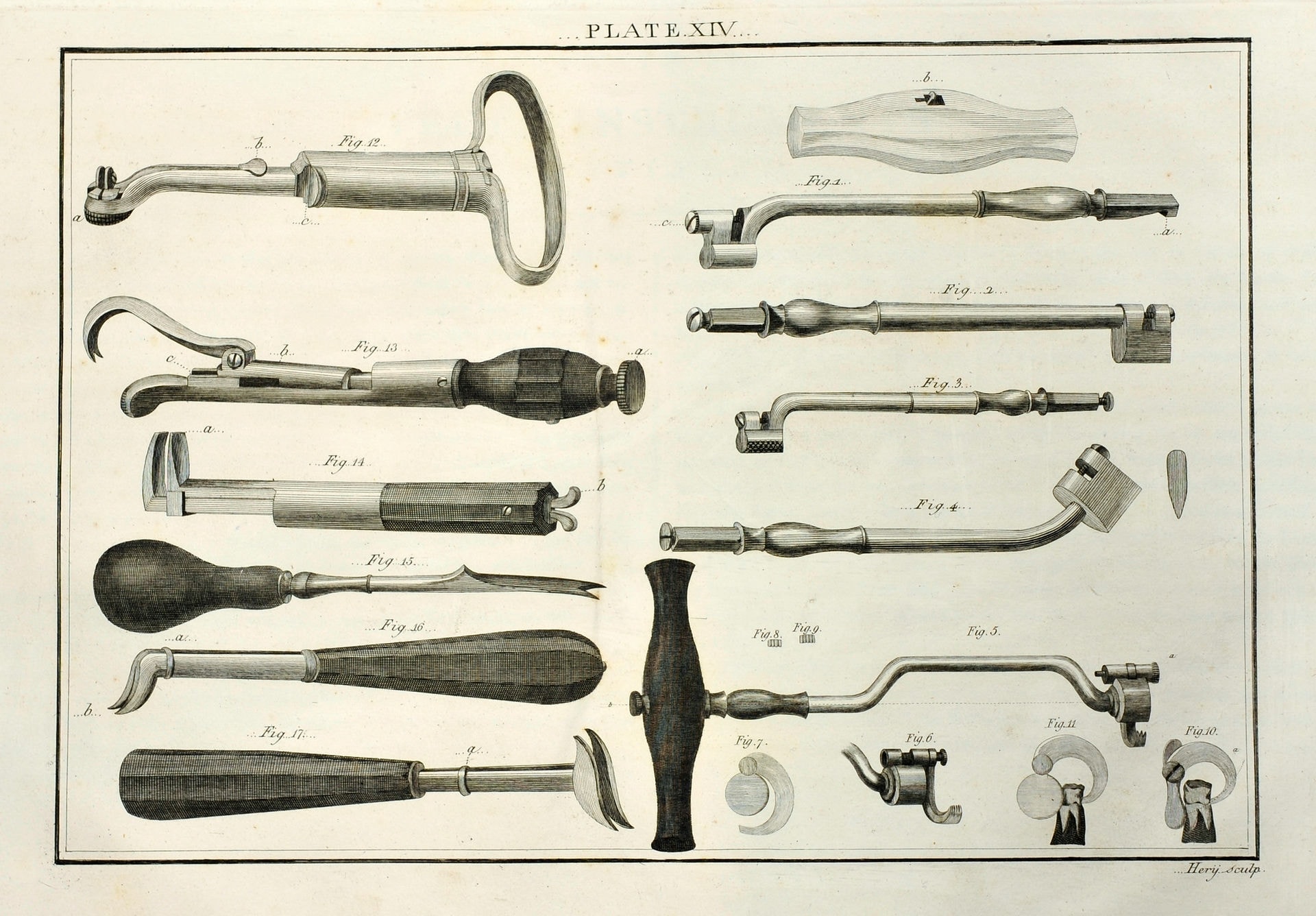

Modeled after a door key, the dental key was used by first inserting the instrument horizontally into the mouth, then its “claw” would be tightened over a tooth. The long metal rod, or bolster, was placed against the root. The instrument was rotated to loosen the tooth and pop it out.

This did not always go so smoothly, but often resulted in the tooth breaking, causing jaw fractures and soft tissue damage.

The Early Tooth Key

The first mention of the tooth key was found in Alexander Monro’s Medical Essays and Observations in 1742. The design of the dental key evolved over the years. Initially, tooth keys were made of metal, typically iron or steel, and featured a handle for the dentist to grasp and a pointed end with a loop or hook to fit over the tooth. It’s important to remember

The original design featured a straight shaft, which caused it to exert pressure on the tooth next to the one being extracted. This led to a newer design in 1765 by Ferdinand Julius Leber, in which the shaft was slightly bent.

A portrait of trailblazing dentist Sir John Tomes.

In 1796, the claw was fixed via a swivel enabling it to be set in various positions by a spring-catch. Newer designs, such as those manufactured by medical instrument maker Charriere featured interchangeable claws. The handle unscrewed and there was a screwdriver inside it with which to change the claw.

Sir John Tomes and the Introduction of Forceps

By the end of the 19th century, the introduction of forceps made popular notably by Sir John Tomes, rendered the tooth key mostly obsolete. His innovative design incorporated ergonomic handles and specialized tips that could grasp different types of teeth securely. This advancement significantly improved the success rate of tooth extractions and reduced the discomfort experienced by patients.

Over time, dental forceps underwent refinements and modifications to suit the evolving needs of dentists and patients. Different designs were developed for extracting specific teeth, with variations in size, shape, and angle to accommodate various dental conditions. Today, dental forceps remain essential tools in every dentist’s arsenal, used for a wide range of procedures from routine extractions to more complex dental surgeries

Despite these advances in dental technology, a modern version of the dental key, the Dimppel Extractor, briefly found popularity and revitalized its use later in the 20th century. Invented by Dr. Karl Dimppel, a German dentist, this tool was designed to aid in the extraction of teeth with curved or irregular roots.

The Dimppel Extractor featured a specialized mechanism that allowed dentists to grip the tooth securely while minimizing trauma to the surrounding tissues. Its innovative design incorporated a series of adjustable components, including a curved shaft and a locking mechanism, which provided greater control and precision during extraction. Dentists could customize the extractor to fit the unique contours of each tooth, resulting in smoother and more efficient extractions.

Despite its initial success, the Dimppel Extractor gradually faded from use as dental technology advanced and new extraction techniques emerged.

Thankfully, dental health has come a long way from the days when Dr. Taylor earned the nickname “The woman that pulled teeth” and the tooth key is now a museum oddity, but women dentists are no longer seen as unconventional.

An illustration of dental keys for tooth extraction from Savigny’s catalog of surgery implements, circa 1798.