Have you brushed your teeth with Sozodont lately? Do you think the local drugstore still carries Rubifoam? Can you find a listing for Dr. Sheffield’s Antiseptic Creme Dentifrice in the pages of Benco Dental’s Dentist’s Desk Reference?

The aforementioned dental products were popular around the turn of the 20th century, but today are almost unheard of. What were these products and what happened to them? Read on to find out:

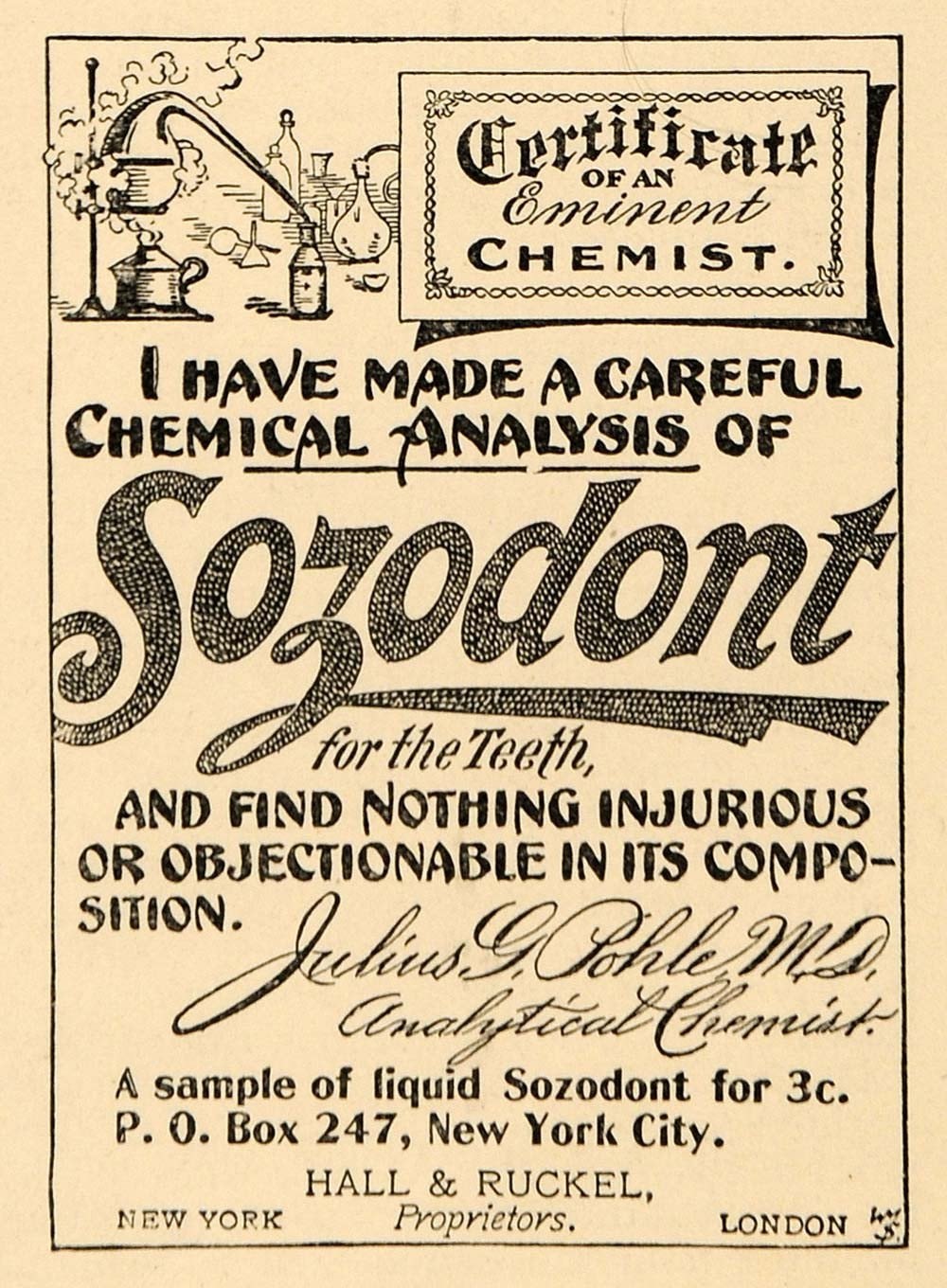

Sozodont

This early tooth cleaner was sold in liquid form. The name references the Greek sozo, meaning “to save”, and dontia, meaning “teeth.” Created in 1859, it was heavily marketed throughout the latter half of the 19th century and into the early part of the 20th century. So well marketed was Sozodont that by the turn of the century, it was a household name, despite its dubious health claims.

The company claimed that Sozodont would clean and preserve the teeth and harden the gums, as well as “impart a delightfully refreshing taste and feeling to the mouth.” In addition promotional material stated: “it prevents the accumulation of tartar on the teeth and arrests the progress of decay.”

None of these claims could be proven. As early as 1866, “The Dental Cosmos” was skeptical of Sozodont and other products like it.

Sozodont grew in popularity until the early 20th century, when it fell out of favor due to issues regarding its side effects.

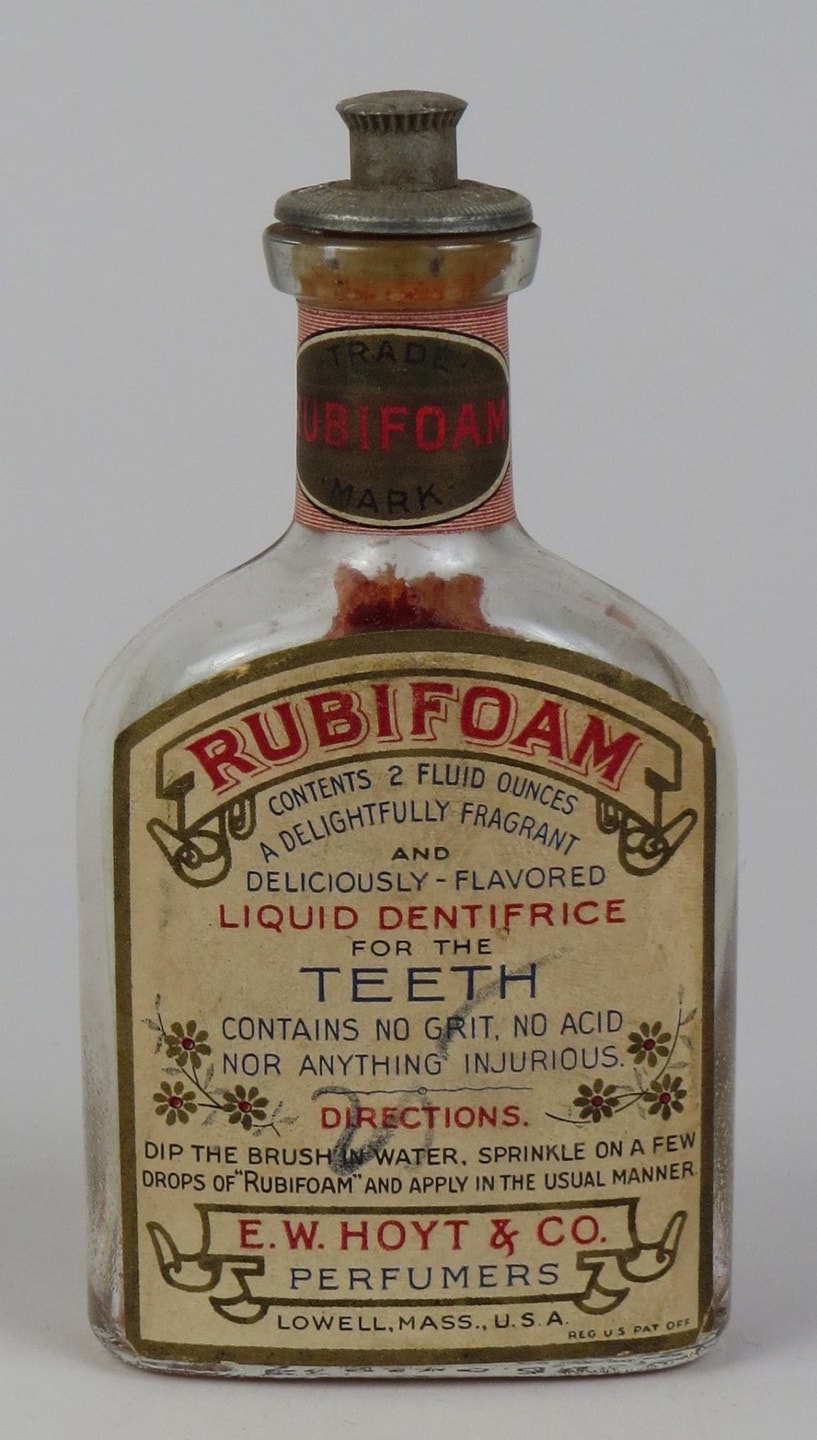

Rubifoam

Another early liquid tooth preparation was created and sold by E.W. Hoyt & Co. in 1887. Called Rubifoam due to the red color of the product, it similar in ingredients to many other “tooth washes” on the market at that time.

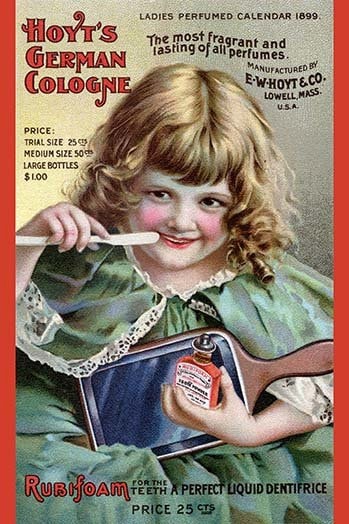

The E.W. Hoyt & Co. was also well-known for producing Hoyt’s German Cologne. The company advocated using Rubifoam to prevent tooth decay, even though, at the time, the cause of tooth decay was still being debated.

The E.W. Hoyt & Co. was also well-known for producing Hoyt’s German Cologne. The company advocated using Rubifoam to prevent tooth decay, even though, at the time, the cause of tooth decay was still being debated.

Why were several of these products colored red? Our ancestors liked their tooth cleaners to match the healthy color of gums, rather today’s toothpastes which mirror the whiteness of teeth.

The Hoyt company’s big seller was the cologne, but the company wisely tied the Rubifoam advertising to the cologne, often creating colorful, collectible cards with both products on them.

The Hoyt company’s big seller was the cologne, but the company wisely tied the Rubifoam advertising to the cologne, often creating colorful, collectible cards with both products on them.

As a result, the “deliciously flavored” (as one advertisement put it) product sold well. Since the ingredients were not super-effective in removing decay, it’s popularity died out as it was replaced with more potent products.

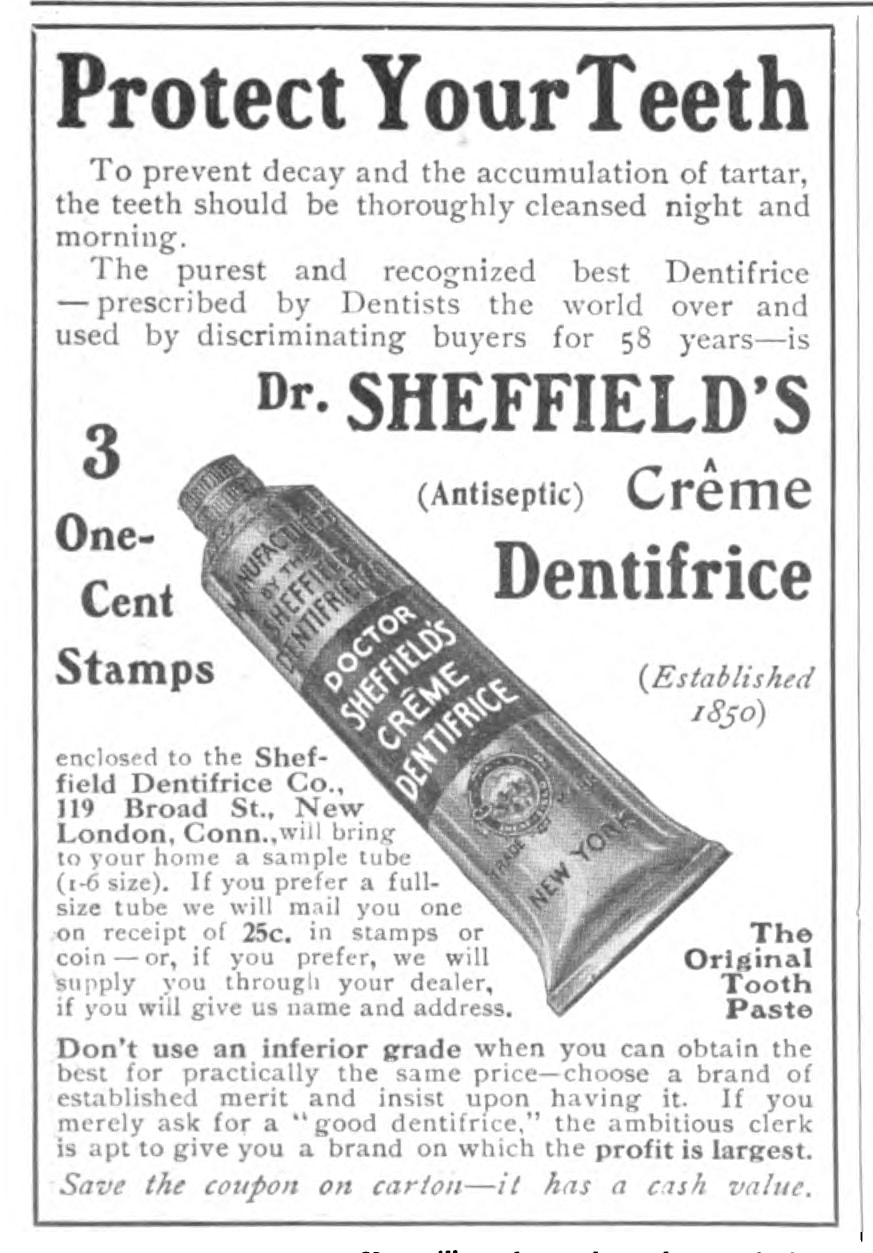

Dr. Sheffield’s Antiseptic Creme Dentifrice

This was an early toothpaste, but with several innovations that set it apart from other early preparations. It was created in the mid 1870s by Dr. Washington Sheffield, a talented dentist located in Connecticut.

This was an early toothpaste, but with several innovations that set it apart from other early preparations. It was created in the mid 1870s by Dr. Washington Sheffield, a talented dentist located in Connecticut.

In addition to having made important contributions to the fields of Dentistry and Dental Surgery, Dr. Sheffield is credited with being the first person to put toothpaste in a collapsible tube. He gave it to his patients and the demand was so strong he started a company, Sheffield Dentifrice Co., which is still in business today as the Sheffield Pharmaceutical Co.

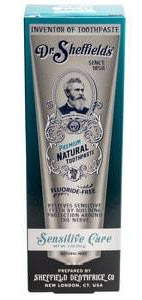

This product can still be bought at your local drugstore!

CVS still carries several varieties of Dr. Sheffield’s toothpaste, including Dr. Sheffield’s Premium Natural Sensitive Care Toothpaste, so it seems that the good doctor was on to something.

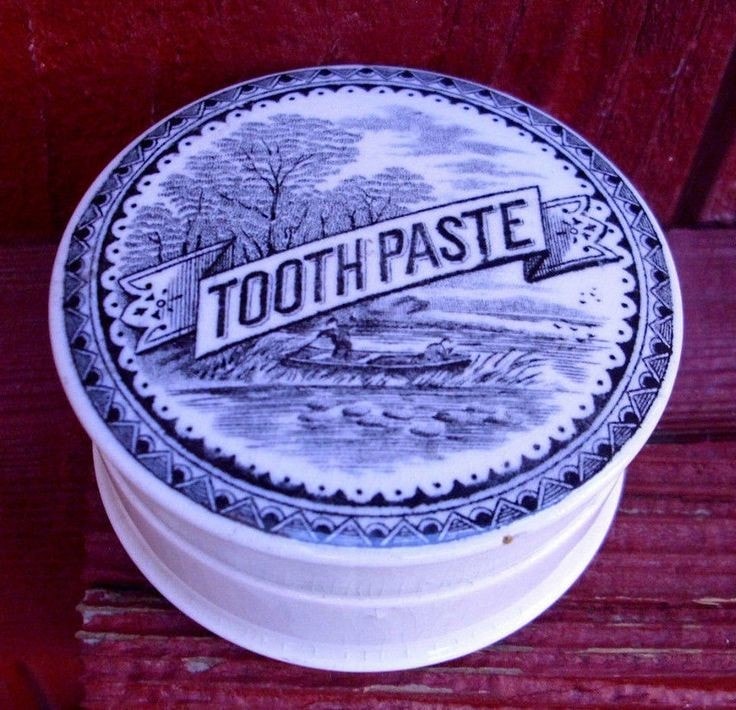

In an era before the Pure Food and Drug Act, there were many commercial preparations that promised to keep teeth perfectly clean and sound that may have been without merit. What many of them did have, was pervasive and beautiful advertising and packaging that is still collected today.

Vintage dental products such as Sozodont, Rubifoam, and Dr. Sheffield’s Antiseptic Creme Dentifrice offers a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of oral hygiene practices and the marketing strategies employed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These products, once touted for their purported benefits and packaged in beautifully designed containers, reflect the era’s optimism and trust in commercial remedies, despite lacking scientific evidence to support their claims.

Through the rise and fall of these vintage dental products, we not only witness the shifting paradigms in oral health care but also appreciate the enduring allure of nostalgia, as evidenced by the enduring popularity of vintage advertising and packaging. As we reflect on these relics of the past, we are reminded of the importance of evidence-based dental care and the continued pursuit of innovation in promoting oral health for generations to come.