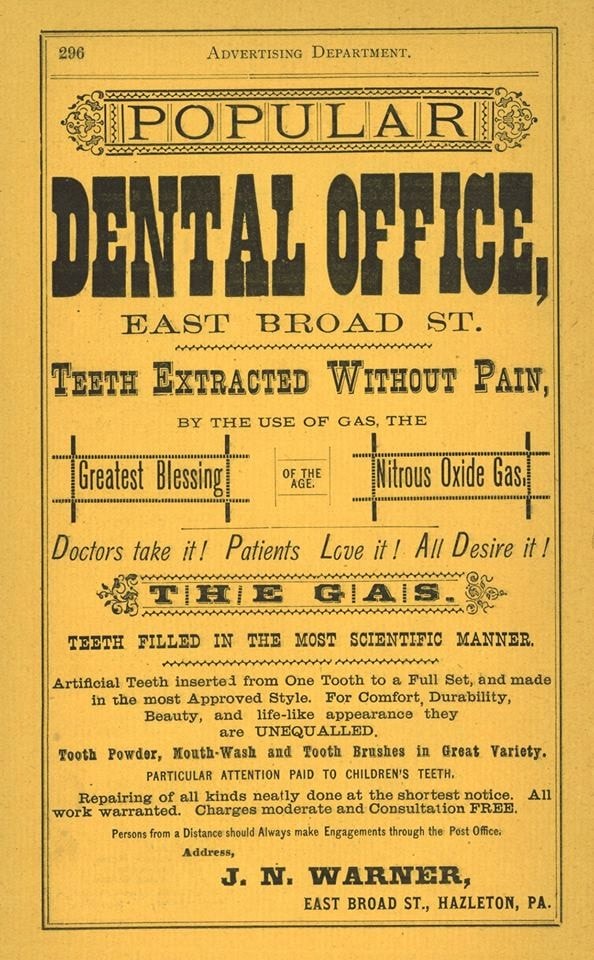

“Doctors take it! Patients Love it! All Desire it!”

So says an advertisement for a Hazleton, Pennsylvania doctor’s office from the 1873 Wilkes-Barre city directory, proclaiming that the doctor uses laughing gas in the painless extraction of teeth.

What is laughing gas, how did it earn its name, and what is its history of use in dentistry?

Laughing gas is actually nitrous oxide, which is nitric oxide that has come into contact with moist iron filings. It was first discovered in 1772 by Joseph Priestly, who confused about the gas, eventually stopped experimenting with it.

1798: Enter an inquisitive 21-year old named Humphry Davy. As director of the Bristol Pneumatics Institute(“pneumatic” – having to do with air), he was charged with trying to find cures for such airborne diseases as tuberculosis. Since nitrous oxide was a gas, he wondered if it could have any effect on a person’s health. He created some gas, collected it in a bag, then stuck his hand (which had a cut on one finger) into it. Nothing happened. He then decided to inhale the gas himself and see what happened. His findings: he became lightheaded and giddy.

After that, he conducted numerous experiments on himself, kept notes of his experiences and convinced many others to inhale the gas, always requiring them to also keep notes of how they felt afterward. He published his findings in a lengthy book in 1800, detailing the history, chemistry, physiology and recreational use of nitrous oxide. Even though he was seeking medical uses for nitrous oxide, the treatise does not mention finding one, except for experimenting on its use with paralyzed patients. Only at the end of his book does he mention his prophetic statement about the possible use of nitrous oxide in surgery:

”As nitrous oxide appears capable of destroying physical pain, it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations in which no great effusion of blood takes place.”

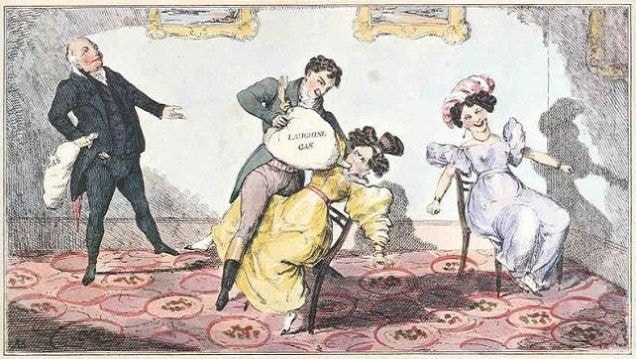

The gas acquired the name “Laughing Gas” due to the frequent feeling of euphoria the gas induced in the people who inhaled it. This led to its being used for more than 40 years as more of a parlor trick than for serious medical purpose. “Laughing Gas” parties became popular in upper-crust circles.

A Regency drug party in full swing.

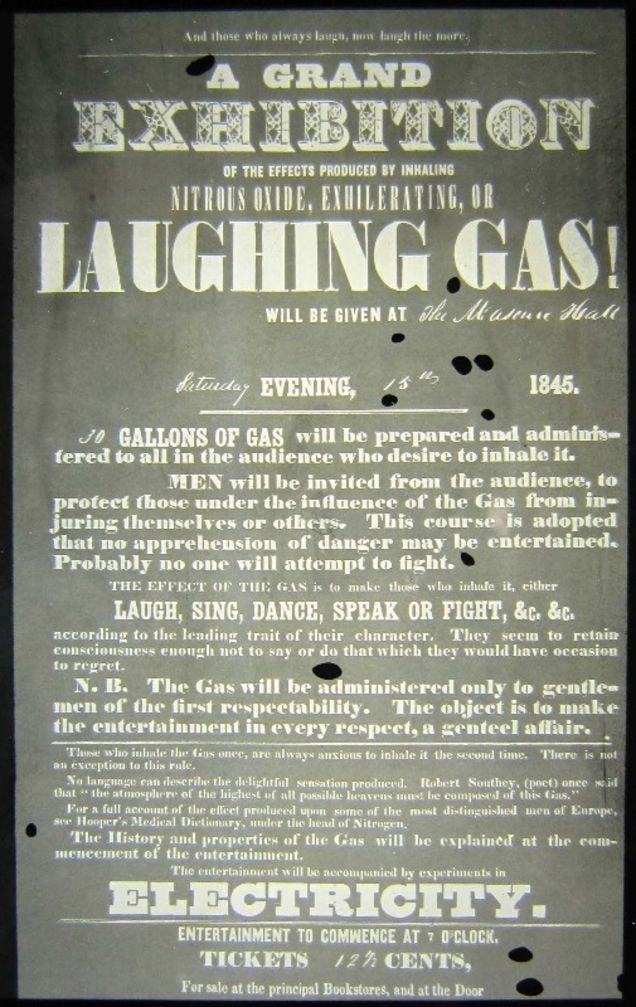

People stopped looking to nitrous oxide as a serious scientific experiment and started using it as a carnival attraction and moneymaker. In the 1840s several people created theatrical shows around administering the gas to willing participants, who laughed, danced and did all manner of silly things under the influence. It was very similar to vaudeville shows where hypnotists offered to make audience members cluck like chickens and bark like dogs.

Would you rather inhale laughing gas or be electrocuted? You had your choice as entertainment in 1845.

At one such “exhibition” a young man, who had been a gas subject, jumped about so violently that he injured his legs. He didn’t seem to mind the pain, though and when he returned to his seat in the audience, a dentist in attendance by the name of Horace Wells took notice. Wells went back to his practice and immediately began using nitrous oxide successfully with his patients. Eager to share his finding with the greater medical community, he set up an experiment in Boston, at the Massachusetts General Hospital. He brought in a patient in need of a tooth extraction, directed the patient to inhale the gas and then pulled the tooth. Unfortunately, the patient probably did not inhale enough of the gas and groaned in pain during the procedure. The experiment looked like a failure and Wells was humiliated out of his practice.

It seemed as though the medical community might miss out on painless surgical procedures.

After Wells’ failure, painless surgery was eventually achieved through the use of ether, demonstrated successfully by a dental student of Wells’: William Morton. Morton performed a surgical procedure on a patient in front of a live audience, as Wells had, only his was more successful. Ether (“twilight sleep” as it was sometimes referred to in the 19th century) became the choice of anesthesia during the mid-19th century.

It took another two decades for a dentist to test nitrous oxide publicly again, and few more decades for the practice to become widespread and effective. Today, nitrous oxide is still used in dentistry. We still don’t even know the exact mechanism of how nitrous oxide works. Our modern understanding of the substance is that it’s fine – but only for medicinal use. What a difference a couple of centuries make.

Top image courtesy of the Lackawanna Historical Society.

Guest blogger Jenn Ochman in Titanic-era garb. Notice, she’s not partaking in laughing gas.