History Lesson

Long before there was ready-made, packaged food for the American military to eat, the soldiers and sailors could count on getting at least one thing in their daily food rations: hardtack.

Two Civil War soldiers photographed with their guns, hardtack, and eating utensils.

…A what now?

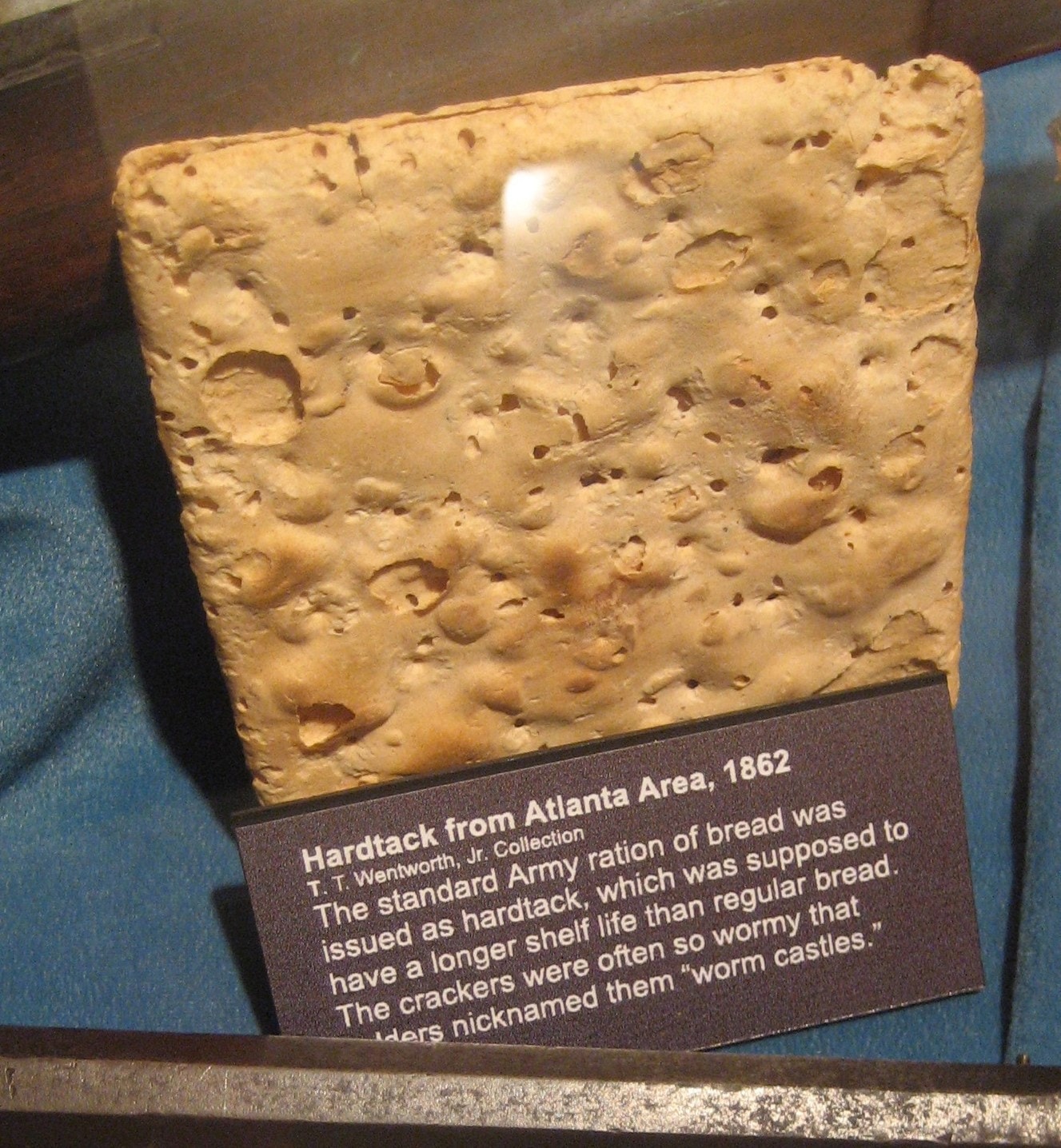

Sometimes referred to as “molar breakers,” due to the hardness of the finishing product, or “worm castles,” because of the tendency to take on bugs, hardtack has been a staple of military rations since before the 19th century.

Were these crackers so hard that you could really break a tooth? Apparently so.

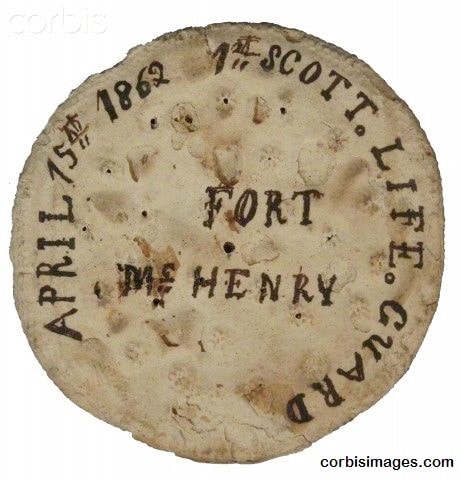

Made using salt, water, and wheat flour, hardtack could provide modest nutrition for a crew at sea or an army in the field for weeks, even months. Their best attribute was that they could be kept indefinitely, as long as they stayed dry. In fact, during the U.S. Civil War, troops were issued hardtack rations — up to 10 a day — that had been prepared for the army during the Mexican War 15 years earlier. The crackers, so hard that some soldiers kept a few as souvenirs after the war, are commonly on display in Civil War museums over 150 years later.

Difficult to imagine how any human beings could consume that many hardtacks each day?

Try eating one. The dryness sucks out any moisture from your mouth. The heavy wafer in your hand feels just as heavy in the stomach. They are so dense, soldiers used them as small plates. And, of course, the flavor is incredibly uninteresting – you’re basically just eating flour.

A Personal Account

Thanks to John Billings’ memoir of his life as a Union soldier, Hardtack and Coffee (1887), we have a very accurate description of what Civil War hardtack rations were like:

“…When the bread was moldy or moist, it was thrown away and made good at the next drawing, so that the men were not the losers; but in the case of its being infested with the weevils, they had to stand it as a rule; but hardtack was not so bad an article of food, even when traversed by insects, as may be supposed. Eaten in the dark, no one could tell the difference between it and hardtack that was untenanted. It was no uncommon occurrence for a man to find the surface of his pot of coffee swimming with weevils, after breaking up hardtack in it, which had come out of the fragments only to drown; but they were easily skimmed off, and left no distinctive flavor behind. …

A Civil War postcard illustrates a soldier breaking a tooth on Hard Tack.

Of course, many of them were eaten just as they were received — hardtack plain; then I have already spoken of their being crumbed in coffee, giving the ‘hardtack and coffee.’ …

Some of these crumbed them in soups for want of other thickening. For this purpose they served very well. Some crumbed them in cold water, then fried the crumbs in the juice and fat of meat. A dish akin to this one which was said to make the hair curl, and certainly was indigestible enough to satisfy the cravings of the most ambitious dyspeptic, was prepared by soaking hardtack in cold water, then frying them brown in pork fat, salting to taste.

Skillygalee, photo courtesy of TimeTravelKitchen

Another name for this dish was skillygalee.

Some liked them toasted, either to crumb in coffee, or if a sutler was at hand whom they could patronize, to butter. The toasting generally took place from the end of a split stick.”