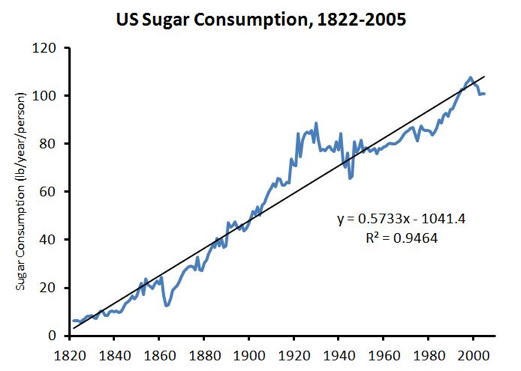

Think about this statistic: in 1900, Americans consumed 90 pounds of sugar per year. By 2008, that number had doubled to 180 pounds per year. The US ranks as having the highest average daily sugar consumption per person. What has happened to our eating habits since 1900?

Think about this statistic: in 1900, Americans consumed 90 pounds of sugar per year. By 2008, that number had doubled to 180 pounds per year. The US ranks as having the highest average daily sugar consumption per person. What has happened to our eating habits since 1900?

Hop in the Wayback Machine

Did they just not have accessibility to sugar in the old days? No, sugar has always been around, mostly in the form of honey or maple syrup. Ancient peoples in countries in the Middle East also learned to develop it from cane stalks. This process eventually worked its way to the West Indies. By the 18th century, the majority of sugar for export was produced in the Caribbean, to be sent to American and England.

But Didn’t We Make Sugar Here?

Didn’t we have sugar plantations here? Sure, but due to the relatively short growing season in the American south, US sugar consumption has always relied on substantial imports. In the decade preceding the Civil War, sugar cane producers in the South supplied only about 1/3 of America’s consumption and the cost of sugar fluctuated periodically. Producing sugar was a labor-intensive operation.

More Sugar, Please!

More Sugar, Please!

Still, with the majority of sugar production coming from the West Indies, and with cheap labor and improvements in mechanization, the cost of sugar over time during the 19th century became more affordable. This was reflected in the change in American diets by the middle of the 19th century. Americans began eating more jams, candy, cocoa, and other sweetened foods.

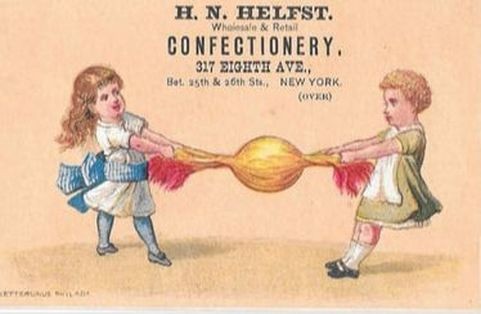

Kids Will Be Kids

Kids Will Be Kids

People in the 19th century are not that far removed from us, in their likes and dislikes. In 1857, The Ohio Journal of Education, Volume 6, described an “Object Lesson” where the children were invited to list “things to be seen”. The results were listed by the teacher on the blackboard. Among the items listed were different types of foods, like meats, pies, and of course, candy. They were children, after all. This gives us a convenient list of candy that children of the mid-19th century liked. And there were many. Among them:

Pop-corn, peppermint, cream, molasses, rose, nut, clove, butterscotch, sugar plums, lemon drops, French kisses, cinnamon, wintergreen, sour drops, hoarhound, gum drops, lavender…

More candy…

As the century wore on, mechanization of candy production and sugar-making improved and sugar became cheaper and more readily available. This meant more candy and sweet stuff available and being consumed by the public. Sugar and candy were presented as pure and good for you.

Is this healthy?

By the 1970s, high fructose corn syrup was introduced into the US food industry and soon became prevalent in many foods, even those that don’t seem to require sweetener, like salad dressings and frozen pizza. High fructose corn syrup is cheap to produce and mimics sugar in its taste and function. Consumption of fructose has climbed steadily since the 1970s, from 37 grams per day to 62.5 grams per day in the early 2000s. This is the start of the “hidden sugar” in American processed food. But is all this sugar entirely healthy? The messaging the American public has been getting regarding our diet since the 1970s has been that fat is bad and sugar is, if not exactly good for us, certainly not bad for us. But is that entirely true…

Enter a Dental Crusader

It seems the Sugar Research Foundation, the sugar lobby that is extremely active in Washington politics, working on behalf of the sugar industry, “has worked to influence the types of research questions that our federal agencies pursue, withheld important knowledge about how our bodies metabolize sugar and skewed research to exonerate their product.” This from Dr. Cristin Kearns in the summer, 2019 Incisal Edge magazine. Dr. Kearns sees herself as a dentist-turned-journalist/crusader. She is featured in the summer issue of Incisal Edge magazine, produced by Benco Dental, where she explains that she was a dentist and director of a public health clinic in Denver. She is now at USCF, working to uncover the truth about how harmful sugar can be for our teeth and our diet.

More Sugar, Please!

More Sugar, Please! Kids Will Be Kids

Kids Will Be Kids